The world on your desktop

location based services

portable navigation devices

Sep 6th 2007 From The Economist print edition

As the internet becomes intertwined with the real world, the resulting “geoweb” has many uses

“EARTH materialises, rotating majestically in front of his face. Hiro reaches out and grabs it. He twists it around so he's looking at Oregon. Tells it to get rid of the clouds, and it does, giving him a crystalline view of the mountains and the seashore.”

That vision from Neal Stephenson's “Snow Crash”, a science-fiction novel published in 1992, aptly describes Google Earth, a computer program that lets users fly over a detailed photographic map of the world. Other information, such as roads, borders and the locations of coffee shops can be draped on to the view, which can be panned, rotated, tilted and zoomed with almost seamless continuity. First-time users often report an exhilarating revelatory pang as they realise what the software can do. As the globe spins and switches from one viewpoint to another, it can even induce vertigo.

Google's virtual globe incorporates elevation data that describe surface features such as mountains and valleys. Other data is then overlaid on it, notably a patchwork of satellite imagery and aerial photography licensed from several public and private providers. The entire planet is covered, with around one-third of all land depicted in such detail that individual trees and cars, and the homes of 3 billion people, can be seen. All this has long been imaginable but has become possible only recently, thanks to high-resolution commercial satellite imaging, broadband links and cheap, powerful computers.

Keyhole, an American firm, released the first commercial “geobrowser” in 2001. Google bought Keyhole in 2004 and launched Google Earth in 2005. Its basic, free version has since been downloaded over 250m times, says Michael Jones, one of Keyhole's founders and now Google Earth's chief technologist.

In 2004 America's space agency, NASA, released another geobrowser, called World Wind. More than 20m copies are in use. But Google's main geobrowsing rival is Microsoft. Both Encarta, Microsoft's encyclopedia, and TerraServer, a database demonstration project, had geobrowser-like features in the 1990s. At the end of 2005 Microsoft bought GeoTango, which contributed to the development of Live Search Maps, a web-based geobrowser that uses data from Virtual Earth, Microsoft's digital model of the planet. (Google also provides a web-based geobrowser via Google Maps.)

An overlay shows desroyed villages in Darfur; sunbakers on Sydney's Bondi Beach; the city of Berlin, with detailed 3-D buildings

Vincent Tao, GeoTango's founder and now director of Virtual Earth for Microsoft, allows that Microsoft has spent at the “couple of hundreds of millions of dollars level” on Virtual Earth. Most of that has been spent on the acquisition of imagery, which now totals 14 petabytes on 900 servers. (One petabyte is 1m gigabytes.) The company is also adding detail in the form of textured three-dimensional models of cities devised from aerial photographs; ten cities are added each month.

For its part, Google is relying on “crowdsourcing”—enlisting its users to build and contribute images, 3-D models of buildings and other data to enrich its digital planet. So far 850,000 users have contributed millions of annotations and more than 1m images, vetting one another's contributions. Wikipedia, which uses a similar system, is itself available through Google Earth. Users can read Wikipedia articles placed on the globe using “geotags”—spatial co-ordinates encoded into each entry. Other sites including Flickr, the leading photo-sharing site, and Google's YouTube, also support geotags.

These virtual globes are being put to an unexpected range of uses. Google Earth was used to co-ordinate relief efforts in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Tax inspectors in Buenos Aires are using it to see whether people are correctly reporting the size of their properties. An Italian programmer who was using the software noticed odd markings on the ground near his home town which turned out to be a previously unknown Roman villa. Roofers, landscape gardeners and solar-panel installers use the virtual maps to scout for potential customers. Rebecca Moore, a member of the Google Earth team, used the software to galvanise her neighbourhood in the Santa Cruz mountains in opposition to a nearby logging project. And the Amazon Conservation Team, an American charity, equipped 26 indigenous tribes in the Amazon with hand-held global positioning system units and computers running Google Earth, to enable them to assert their legal sovereignty in the face of threats from loggers and miners.

“It's turning into a map of historical significance,” says John Hanke, head of Google's Earth and Maps division, and another of Keyhole's founders. “It is going to be a map of the world that is more detailed than any map that's ever been created.” He may be understating the technology's importance.

The world-wired web

Geobrowsers are a stunningly effective means of visualising the planet. But they are just one part of a broader endeavour, the construction of a “geoweb” that is still in its infancy, much as the world wide web was in the mid-1990s. The web did away with many geographical constraints, enabling people with common interests to communicate, regardless of location. Yet placelessness jettisons some of the most useful features of information, which are now attracting new attention.

At present the most feverish excitement surrounds the combination of virtual maps with other sources of data in “mash-ups”. One of the earliest examples, housingmaps.com, created in 2005, combines San Francisco apartment listings from Craigslist.org with Google Maps. Mash-ups have since become commonplace—Google says its maps are used in more than 4m of them. In April the company added features to Google Maps to make it easier to create mash-ups. Microsoft is at work on a similar tool. Another site, platial.com, provides free mash-up tools for bloggers, spawning a new genre in self-absorption: autobiogeography.

The geoweb has obvious appeal to those in the property business. Zillow.com mashes Microsoft's Virtual Earth with other data to create maps of home prices in America. But property is just the start. At gasbuddy.com, visitors can map local petrol prices to plan fill-ups. ExploreOurPla.net brings together thousands of sources of images and data to let users investigate climate change.

House prices overlaid on a satellite map at Zillow.com; San Francisco, seen on Google's Street View; a GIS view of an air-force base

These examples illustrate the emerging architecture of the geoweb: data, such as information on traffic jams or seismic tremors, is hosted separately from the images and models of the geobrowser, which assembles, combines and displays the information in new ways. GeoCommons.com hosts data, from crime rates to melanoma statistics, that can be combined to create colour-coded “heat maps” of intangibles such as “hipness”. Visitors to Heywhatsthat.com can generate a diagram of the view from any high spot to see the names of visible mountain peaks.

Here the neogeographers, as mash-up enthusiasts are known, have crossed into the terrain of “geographic information systems” (GIS), the fancy software tools that are used by governments and companies to analyse spatial data. Geobrowsers are still quite primitive by comparison, but are much easier to use. For its part GIS deals with critical infrastructure, so its data tend to be of impeccable quality. Jack Dangermond, the founder of ESRI, a private firm that dominates the GIS market, says interest stimulated by the geoweb has helped to boost business by 20% this year. Ron Lake of Galdos Systems, a firm that specialises in integrating civic geodata, says geobrowsers have led to a push for better public access to such data.

When the analytical insights and data quality of GIS are combined with the geoweb's visualisation and networking prowess, startling efficiencies emerge. Last year Waterstone, a consultancy, assembled the geodata for 13 American air-force bases and wrapped them up in a modified version of NASA's World Wind geobrowser. This makes it possible to walk through a 3-D model of each base and call up multiple layers of data. A project manager can view live video from a construction site and identify the contractors and their vehicles. A planner can assess a proposed building's effect on runway visibility. And an environmental engineer, while viewing a plume of contaminated groundwater, can delve into 45 years' worth of documents associated with the site. Carla Johnson, Waterstone's boss, says the project cost less than $1m and is expected to save the air force around $5m a year through faster decision-making.

Smile, you're on Google Earth

Like any technology, the geoweb has both good and bad uses. When geobrowsers first introduced easy access to satellite imagery, something that had previously only been available to intelligence agencies, many observers worried that terrorists might use such images to plan attacks. Google Earth seems to have been used in this way by Iraqi insurgents planning attacks on a British base in the city of Basra, for example, in which individual buildings and vehicles can be clearly seen. After this came to light in January, the images of the area in question were replaced with images from 2002, predating the construction of the camp.

This summer a member of the Assembly of the State of New York called on Google to obscure imagery after the geobrowser was used by plotters in a foiled airport attack. Yet Mr Jones says Google has been formally contacted by governments in this regard only three times (including by India and by an unspecified European country), and that in each case the issue was resolved without making changes to the imagery in Google Earth.

Although some buildings or areas are blurred for security reasons, Google says this is done by the firms from which it licenses the imagery. Microsoft says it blurs photos in response to “legitimate government and agency requests”. But the images are typically between six months and three years old, which limits their tactical usefulness; and satellite and aerial images are available from many other sources, and have been for some time. So in some respects, geobrowsers have not made possible anything that was not possible before—they have just made access to such images much cheaper and easier.

“It's a question of the policy and the thinking catching up with the technology,” says Mr Hanke. “Ease of access alters the debate.” Google insists that it takes security concerns very seriously, and points out that the American government's official position is that the benefits of making satellite images widely available outweigh the risks. Indeed, some jurisdictions are embracing the exposure. The Canary Islands have donated high-resolution imagery to Google in the hope that virtual visitors might become real tourists, and the city of Berlin has made its painstakingly detailed digital models available through Google Earth.

For governments that are used to hiding things from each other's spy satellites, the advent of the geobrowsers does not change things very much. Ordinary members of the public can now call up images of Chinese nuclear submarines via Google Earth, but intelligence agencies around the world have had access to far more detailed satellite images for years. And the fact that the submarines can be seen at all means that China is not trying to keep their existence a secret. Even so, armed forces do find the geoweb useful. The American military is a big user of both World Wind and the enterprise version of Google Earth. And some governments do have grounds for concern: the government of Sudan, for example, would undoubtedly prefer the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum not to highlight destroyed villages in Darfur via an overlay in Google Earth.

Close to home, the geoweb turns out to have implications for personal privacy as well as geopolitics. Google's new Street View feature, launched in May, lets users of Google Maps move through stitched-together street-level imagery of several American cities, giving private citizens a taste of “crowdsourced” surveillance. All the views are of public streets yet, in aggregate, they challenge accepted notions of privacy—especially for those caught doing something naughty as Google's specially equipped camera van swoops past. Shortly after the feature was launched, users uncovered a car getting a ticket from Miami police, a man scaling a locked gate in San Francisco and another man entering a shop selling sex toys.

“When the coverage is everything and everywhere, there is going to be a big problem,” says Lee Tien, a lawyer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, an internet campaign group. Satellite images are not detailed enough to allow individual people or vehicles to be identified, but faces and licence plates can be seen in Google's Street View. There are few legal precedents. In 2003, Barbra Streisand sued to keep her Malibu estate out of an online library of images of the California coast. She lost. Although movie stars are more stalked than most—several sites provide geobrowser links to celebrities' homes—it is easy to imagine innocent annotations that could be unintentionally dangerous. Shelters for battered women, for example, often prefer not to make their locations widely known.

Google's Mr Jones believes the benefits are strong enough to overcome these concerns. “I think there's a social barrier to everything new,” he says. The availability of useful information will outweigh concern over surveillance and loss of privacy, he believes. Five or six years ago, he notes, people worried about the spread of camera phones. But now “everyone just presumes that everybody has a camera on their phone—it's nothing special.” The lesson of previous technologies, he says, is that “we all are happy to tolerate things that would have previously been considered intolerable.”

Indeed, all the features—good and bad—of the internet will eventually gain new dimensions on the geoweb. Bots and intelligent agents will crawl it. It will be populated by avatars, as Second Life becomes first life, and it will enable the inverse: telepresent machines roaming the real world. Ghostly, private worlds will be overlaid on reality, sensitive only to members. The malicious possibilities are sobering: location-based viruses, geohacking and, worst of all, geospam.

Despite these concerns, the potential of the geoweb is not lost on investors. Since the beginning of last year more than 20 geospatial firms have been the targets of mergers and acquisitions, with Google, Microsoft and ESRI among the buyers. But it is not quite time to declare the dawn of Web 3.0. For one thing, consumer geobrowsing does not make any money. Microsoft's Mr Tao says that revenue has to come from advertising for now, until critical mass enables location-based transactions. Google, true to form, is investing first and worrying about revenue later.

The road to Web 3.0

A more immediate hurdle is on the verge of resolution. Google recently submitted KML, the tagging protocol that describes how objects are placed in Google Earth, to the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC), a standards body. This will let other firms support it. GML, a protocol developed by the OGC to encode spatial-information models, was formally adopted as an international standard this year. Standards for dynamic geodata, the sharing of 3-D models of buildings and geodata from sensor networks ought to be in place by next year. All this will ensure interoperability and do for geodata what the web did for other forms of data, says Carl Reed, the OGC's chief technologist.

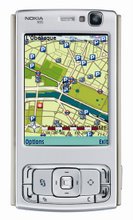

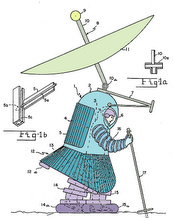

At the same time, the incorporation of satellite-positioning technology into mobile phones and cars could open the floodgates. When it is available, simply moving about one's neighbourhood can then be tantamount to browsing and generating content without doing anything, as demonstrated by a company called Socialight. Its service lets mobile users attach notes to any location, to be read by others who come along later. Taken further, the result could end up being a sort of extrasensory information awareness, annotation and analysis capability in the real world. “When that happens”, says Mr Jones, “then the map is actually a little portal on to life itself.” The only thing that can hold it back, he believes, is the rate at which society can adapt.

printStorySection = 'technology quarterly';

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment