Take 5: The Evolution Of The Mobile Phone User Experience

location based services

Posted by Stephen Wellman, Apr 24, 2007 05:13 PM

Welcome to this week's edition of Take 5, our regular feature on Over The Air where we ask a wireless or enterprise IT industry insider five (or in this case eight) questions about a specific area of interest. This week's guest is Frank Tyneski, Senior Director of Design and Human Factors for Kyocera Wireless. Our topic is The Evolution Of Mobile Usability, with an emphasis on handsets and smartphones. Let's dig in.

What are the biggest challenges to making a mobile phone easier to use?

I believe the biggest challenge is constantly reminding yourself (as a manufacturer) that you’re not designing phones for your industry technology peers. Mass market consumers -- and this includes business users as well as consumers -- who purchase mobile phones are seeking simplicity. Anything beyond the basic functions can compromise what is really important to them. The real challenge lies in understanding what customers want within various user segments and then inserting increased functionality without compromising their core usability desires. We're solving this equation by putting a heavy emphasis on the integration of research and design. In many cases, we are placing designers in the field and actually designing on location with target consumers to develop a better context of understanding for particular user groups and the environments in which they live, work and play.

After years of talk and endless hype, we know that people are using their mobile phones to do all kinds of tasks including text messaging, checking their e-mail, downloading ringtones, and even surfing the Web. But many users still complain about the user experience on their handsets. Many wireless industry insiders claim we're hitting a glass ceiling of mobile usability -- i.e. that the devices can't really do more than they do now (if they can even do that). Do you agree with this assessment?

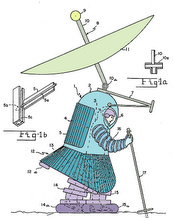

Five years ago, the wireless shows like CTIA and 3GSM were peppered with forward-thinking concepts – essentially, non-working appearance models showing grand visions of the future. Back then, the industry’s future trajectory was visible to the general public. We've since realized those original visions, climaxing today with mobile music, TV, GPS, and more on relatively small devices. Now, manufacturers have shifted their vision and strategy toward convincing consumers that they can, in fact, deliver a complex group of wireless utilities with more grace and expertise than their competitors.With future wireless concepts being less celebrated, there is a perception that the industry has hit a flat spot. However, in this case, perception is not reality. The mobile communications industry continues to be the equivalent of our 'jet age.' In comparison, I think we’ve only developed the propeller. This is not to say that mobile communications won't evolve to reveal some common denominators, but I think we're many years away from that. The key is that it's not just about manufacturers advancing handsets in a silo while content providers and infrastructure providers make advancements in their silos. We, as an industry, need to pay particular attention to developing holistic user experiences, where devices, applications and infrastructure work harmoniously. This is the glass ceiling we’re pressing against, with much compression. I suppose it’s a good thing the glass is not in a fixed frame. It's continually being pushed upward, just not as quickly as some would like.

Do you think the iPhone will be the tipping point for improved mobile User Input? Or does the iPhone represent a transition phase?

The iPhone appears to be a compelling device and I'm looking forward to playing with one. It's premature, however, to say that it's going to recalibrate consumer expectations of a mobile phone. The iPhone is likely to push the envelop for consumers by mixing increased processor speeds with the organic, elegant and charming user experience people have come to expect from Apple. But we cannot forget that it's being talked about as a $500 device and that will keep it out of the hands of a vast majority of consumers. The challenge for phone manufacturers, including my team at Kyocera, is to remove price as a barrier to consumers who want an organic, charming and elegant user experience. I want to create phones that use design, features and user interface to make the devices extensions of their users and a part of those users' lifestyles.

"Latency kills the mobile experience." I don't know about you, but I totally agree with this opinion. But, as people in the wireless industry, like you, know latency will always be a fact with mobile networks. What can you do, in terms of UI and UE, to reduce the impact of latency in the end-user experience?

Well, the short answer is to play tricks -- create the illusion of high speed whenever possible. Cached images and animations can reduce the perceived time from the initiated request to delivery. For example, your Internet favorites could display cached images of your last visit, which are refreshed periodically, when the phone is idle. Or better yet, turn latency into an opportunity, such as turning Push-to-Talk into Push-To-Message, or PTM. It would be great to just send someone a voice message, forgoing actually talking to them, assuming I don't have time, or suffering through their lengthy voicemail message. In this case, the latency entering in text would be displaced by the expediency of voice with all the inflection of your character, not to mention that there would be chronology, something PTT doesn't offer.

Many people may not know this, but you were involved with the design of the BlackBerry Pearl. How did you go about rethinking the BlackBerry UI paradigm? And can this thinking apply to other smartphones?

Well it’s more accurate to say that before coming to Kyocera Wireless I was responsible for leading RIM into the consumer space with the 7100 series of products with SureType. The success of the 7100 series eventually led to the most recent design, the Pearl. RIM is a wonderful company; it's a place where forward-thinking ideas are supported by brilliant people. The SureType text entry UI is an example of what could be and was created in that type of culture. And it's a similar mindset that attracted me to Kyocera. I've never been a fan of mobile convergence. That’s because convergence is too often approached in this way: take human-scaled input mechanisms (like a full-sized QWERTY keyboard, etc.) and dump them into the wide end of the funnel, then apply pressure. Squeeze and squeeze until a "converged" device pops out from the narrow end of the funnel. The result is a severely compromised converged device. The SureType UI was not designed in this way. Quite the opposite in fact, we turned the convergence funnel upside down with scaled input mechanisms serving as the root system -- thereby allowing a whole new UI paradigm to blossom. Personally, I believe more innovation would come from the mobile community if manufacturers approached it in this way. It's a mindset I've brought with me and try to instill in my team. Ultimately, it's about innovation, not just convergence.

What are the differences between designing a mobile device for the business market vs. designing for the consumer market? What kinds of features do business users need vs. those that consumers want?

Actually, business users and consumers are more alike than different -- it's their purchasing behavior that is most different. For example, the business/enterprise user approaches the product purchase with a well-defined set of classical and rational values. Enterprise users are more inclined to research their next purchases, deciding on things such as applications, battery life, integration with other office tools and deployment on the corporate network. Under these conditions, cost and product styling are less important. For example, an ultra-slim enterprise device with poor battery life would be a deal breaker, no matter how inexpensive it was. In contrast, young consumers are the opposite. Their world revolves around instant gratification. They place a greater emphasis on the emotional attributes of a product, including design, color, material and trend overlays. Show a 'millennial' [someone between the ages of 13 to 24] something cool and they’ll likely respond, "I like it, I want it, what is it?"

If you were going to re-design an existing smartphone how would you begin?

I learned early on in my career, back when I was a toy designer for Fisher-Price, that the best ideas are never prescribed. The best results came when the design briefs were vague with a heavy emphasis on "play value." I still approach every new product category in this way. It helped me to later design the first Nextel phone and the TalkAbout two-way radios for Motorola. Whenever possible, I suggest designers spend time seeking out the unexpected. With that said, I couldn't begin to tell you what the end result would be for a redesigned smartphone, but rest assured I guarantee it wouldn't be a refresh of the phones you see on shelves today.

Do you have a favorite mobile OS? Windows? Palm? Symbian? BlackBerry? Linux? What do you think would be the hallmarks of the next generation mobile UI?

Naturally I'm eager to try the iPhone and I have some sentimental attachment to the BlackBerry. At Kyocera, though, we've taken a step back from these operating systems and really focused our efforts on creating a tighter integration between the device and the UI experience.

Today's challenge is in bridging the distance between those designing hardware and those designing the user interface. The difference between universal UI and custom UI is becoming more apparent in the phone experience. As devices continue to advance, carriers will need to elevate their UI expectations to compete on equal footing -- placing more pressure on handset manufacturers and developers to not just collaborate but cohabitate

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment