| By Rebecca Morelle Science reporter, BBC News, Sisimiut |

Danish scientists are to put satellite tags on walruses to try to understand where the great beasts migrate.

The satellite data will be shared with BBC News and posted on its website so readers can follow the migration.

The animals will be tracked for two months off west Greenland - and gauge how hunting, oil exploration and climate change may be affecting them.

The project is being run by the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources and the Danish Polar Centre.

![]()

![]()

![]()

At this time of year, west Greenland's walruses are lazing around on pack ice, basking in the early spring sunshine.

But as temperatures rise further, the ice will begin to retreat, and the mammals will soon be heading north to colder climes. The exact location of their summer hideaway has long been a mystery.

"We want to find out where they are going," explains Professor Erik Born, the senior scientist in charge of the project.

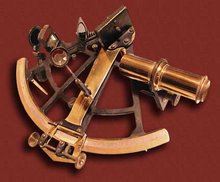

And to do this, he plans to employ Global Positioning System (GPS) technology.

Tagging from afar

I will be joining the Danish team as it leaves the port of Sisimiut, travelling north by trawler along the coast.

During two weeks at sea, the researchers hope to attach 10 satellite tags to walruses.

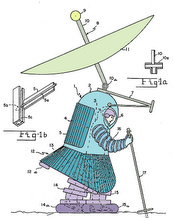

The devices will be deployed using a cross bow or CO2-powered gun fired from the boat.

Although this method might sound cruel, you have to remember that walruses have a hide that is about 2-4cm (0.8-1.3in) thick, Professor Born says.

Each time the tagged creatures emerge from the water, a signal will be beamed up to a satellite, allowing the walruses' coordinates to be determined.

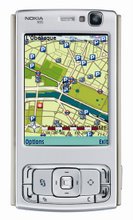

The researchers will watch the walruses' day-to-day progress - as will readers of the BBC News website on its Walrus Watch map.

The tags will stay on for one to two months, eventually being pushed out as the hide heals. The team believes the time period should provide enough data.

Who's who?

This will be the third spring in which Professor Born's team has tracked the animals. "They are fascinating creatures," he tells the BBC News website.

There are at least two sub-species of walrus: the Pacific walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens), found in the Bering Strait region, off Alaska; and the Atlantic walrus ( O. rosmarus rosmarus), found in eastern Canada and the high Arctic.

Some believe walruses in the Laptev sea off Siberia are another sub-species, but this has not yet been confirmed.

They are bulky beasts, weighing up to two tonnes, with tusks that can grow to 80cm (30in) in length.

The animals of central west Greenland that Professor Born and his team plan to track form one of at least eight separate sub-populations of Atlantic walruses.

One of the issues the scientists are hoping to resolve is whether these walruses are connected with other populations.

"We suspect they have a connection with walruses that occur along Eastern Baffin Island. Alternatively, they might be connected with those that occur year-round in northwest Greenland," Professor Born explains.

This information could have an impact on another concern: hunting.

Walruses make an easy target for hunters. Though graceful and swift in water, their lumbering gait on land has made them an easy kill.

Over the last 500 years, they have been exploited for their blubber, hide, ivory and meat, bringing some populations to the brink of extinction.

Today, although some walrus populations are protected, those that live around the coasts of Greenland and Canada are still hunted for their ivory and meat. ![]()

![]()

Professor Born believes there may be over-exploitation of some groups.

"If there is a connection between the walruses of Greenland and Canada, and they are both being heavily hunted, then this could have an impact on sustainable numbers."

The researchers also plan to see how the walruses are affected by local oil exploration.

The animals feast on bivalve species on the sea bed, but some of these vital feeding banks are found in areas that are also proving to be of interest to the oil industry.

Climate changes

And, as with all polar creatures, there is the issue of climate change.

Because of rising temperatures, the edge of the pack ice is moving further north. This could spell trouble for some populations.

"The molluscs walruses feed on are confined to relatively shallow waters," says Professor Born.

"Either the walruses can follow the pack-ice north, and stay over deeper waters where they cannot feed; or they could stay behind in open water without a chance to haul out and rest between their feeding." ![]()

![]()

This could be especially problematic for Pacific walruses, he adds. On the other hand, the Greenland groups may be luckier.

"Atlantic walruses can haul out on land if there is no ice. They have an alternative."

And, unlike the walruses of the Bering Strait, their feeding banks are closer to land, meaning they may manage quite well if the ice goes into a rapid retreat.

The Danish team plans to run the tagging experiments over a number of years.

We hope to have the mapping data up on the BBC News website in the next couple of weeks.

It is not clear whether the Laptev walrus is a separate subspecies |

No comments:

Post a Comment