Russia Challenges the U.S. Monopoly on Satellite Navigation

location based services

ANDREW E. KRAMER

MOSCOW, April 3 — The days of their cold war may have passed, but Russia and the United States are in the midst of another battle — this one a technological fight over the United States monopoly on satellite navigation.

By the end of the year, the authorities here say, the Russian space agency plans to launch eight navigation satellites that would nearly complete the country’s own system, called Glonass, for Global Navigation Satellite System.

The system is expected to begin operating over Russian territory and parts of adjacent Europe and Asia, and then go global in 2009 to compete with the Global Positioning System of the United States.

Nor is Russia the only country trying to break the American monopoly on navigation technology. China has already sent up satellites to create its own system, called Baidu after the Chinese word for the Big Dipper. And the European Union has also begun developing a rival system, Galileo, although work has been halted because of doubts among the private contractors over its potential for profits. Russia’s system is furthest along, paid for with government oil revenue.

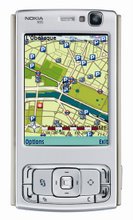

What is driving the technological battle is, in part, the potential for many more uses for satellite navigation than the one most people know it for — giving driving instructions to travelers. Businesses as disparate as agriculture and banking are integrating it into their operations. Satellite navigation may provide the platform for services like site-specific advertising, with directions that appear on cellphone screens when a user is walking, for example, near a Starbucks coffee shop or a McDonald’s restaurant.

Sales of G.P.S. devices are already booming. The global market for the devices hit $15 billion in 2006, according to the GPS Industry Council, a Washington trade group, and is expanding at a rate of 25 to 30 percent annually.

But what is also behind the battle for control of navigation technology is a fear that the United States could use its monopoly — the system was developed and is controlled by the military, after all — to switch off signals in a time of crisis.

“In a few years, business without a navigation signal will become inconceivable,” said Andrei G. Ionin, an aerospace analyst with the Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technologies, which is linked to the Russian defense ministry. “Everything that moves will use a navigation signal — airplanes, trains, yachts, people, rockets, valuable animals and favorite pets.”

When that happens, countries that choose to rely only on G.P.S., he said, will be falling into “a geopolitical trap” of American dominance of an important Internet-age infrastructure. The United States could theoretically deny navigation signals to countries like Iran and North Korea, not just in time of war, but as a high-tech form of economic sanction that could disrupt power grids, banking systems and other industries, he said. The United States government’s stated policy is to provide uninterrupted signals globally.

G.P.S. devices, in fact, are at the center of the dispute over the Iranian seizure of 15 British sailors and marines. The British maintain that the devices on their boats showed they were in Iraqi waters; the Iranians have countered with map coordinates that it said showed they had been in Iranian waters.

Russia’s project, of course, carries wide implications for armies around the world by providing a navigation system not controlled by the Pentagon, complementing Moscow’s increasingly assertive foreign policy stance.

The United States formally opened G.P.S. to civilian users in 1993 by promising to provide it continually, at no cost, around the world.

The Russian system is also calculated to send ripples through the fast-expanding industry for consumer navigation devices by promising a slight technical advantage over G.P.S. alone, analysts and industry executives say. Devices receiving signals from both systems would presumably be more reliable.

President Vladimir V. Putin, who speaks often about Glonass and its possibilities, has prodded his scientists to make the product consumer friendly.

“The network must be impeccable, better than G.P.S., and cheaper if we want clients to choose Glonass,” Mr. Putin said last month at a Russian government meeting on the system, according to the Interfax news agency.

“You know how much I care about Glonass,” Mr. Putin told his ministers.

G.P.S. has its roots in the American military in the 1960s. In 1983, before the system was fully functional, President Ronald Reagan suggested making it available to civilian users around the world after a Korean Air flight strayed into Soviet airspace and was shot down.

G.P.S. got its first military test in the Persian Gulf war in 1991, and was seen as a big reason for the success of the precision bombing campaign, which helped spur its adoption in commercial applications in the 1990s.

The Russian system, like America’s G.P.S., has roots in the cold war technology to guide strategic bombers and missiles. It was briefly operational in the mid-1990s, but fell into disrepair. The Russian satellites send signals that are usable now but work only intermittently.

To operate globally, a system needs a minimum of 24 satellites, the number in the G.P.S. constellation, not counting spares in orbit.

A receiver must be in line of sight of no fewer than three satellites at any time to triangulate an accurate position. A fourth satellite is needed to calculate altitude. As other countries introduce competing systems, devices capable of receiving foreign signals along with G.P.S. will more often be in line of sight of three or more satellites.

Within the United States, Western Europe and Japan, ground-based transmissions hone the accuracy of signals to within a few feet of a location — better than what could be achieved with satellite signals alone. The Russian and eventual European or Chinese systems, therefore, would make receivers more reliable in preventing signal loss when there are obstructions, like steep canyons, tall buildings or even trees.

Still, a Glonass-capable G.P.S. receiver in the United States, Western Europe or Japan would not be more accurate than a G.P.S. system alone, because of the ground-based correction signals. In other parts of the world, a Glonass-capable G.P.S. receiver would be more reliable and slightly more accurate.

American manufacturers that are dominant in the industry could be confronted with pressure to offer these advantages to customers by making devices compatible with the Russian system, inevitably undermining the American monopoly on navigation signals used in commerce.

In this sense, the Russians are setting off the first salvo in a battle for an infrastructure in the skies. Russia sees a great deal at stake in influencing the standards that will be used in civilian consumer devices.

The market for satellite navigators is growing rapidly. Garmin, the largest American manufacturer, more than doubled sales of automobile navigators in 2006, for example, and in February it showed a Super Bowl ad that was seen as a coming of age for G.P.S. navigators as a mass market product.

Jeremy D. Ludwig was one consumer who said he would be willing to pay a slight premium for a device equipped with a chip capable of processing Russian navigation signals.

He recounted a recent trip on Interstate 25 in Colorado, when, he said, he was dismayed to discover the G.P.S. device on his BlackBerry had inexplicably lost its signal, just as he was trying to decide which exit to take into Denver.

“If you don’t know which exit to take, you’re already lost,” Mr. Ludwig, an art student, said in a recent telephone interview from Colorado Springs.

That kind of attitude is what Russia is banking on even as it also takes a stab at making consumer receivers — so far without much success. But the Russian goal of diversifying navigation signals used in commerce will be achieved, Mr. Ionin said, even if foreign manufacturers simply adopt the Russian standard, and even if Russia’s own attempt to make consumer devices fails.

To encourage wide acceptance, Mr. Putin has been pitching the system during foreign visits, asking for collaboration and financial support.

Now, only makers of high-end surveying and professional navigation receivers have adopted dual-system capability.

Topcon Positioning Systems of Livermore, Calif., for example, offers a Glonass and G.P.S. receiver for surveyors and heavy-equipment operators. Javad Navigation Systems is built around making dual-system receivers, with offices in San Jose and Moscow.

Javad Ashjaee, the president of Javad, said in an interview that wide adoption was inevitable because more satellites provided an inherently better service. “If you have G.P.S., you have 90 percent of what you need,” he said. Russia’s system will succeed, he said, “for that extra 10 percent.”

Adding Glonass to low-end consumer devices would require a new chip, with associated design costs, but probably not much in the way of additional manufacturing expenses, he said.

Already this year, in a sign of growing acceptance of Glonass, another high-end manufacturer, Trimble, based in Sunnyvale, Calif., introduced a Russian-compatible device for agricultural navigators, used for applying pesticides, for example.

Whether consumer goods manufacturers will follow is an open question, John R. Bucher, a wireless equipment analyst at BMO Capital Markets, said in a telephone interview.

Garmin, which has more than 50 percent of the American market, has not yet taken a position on Glonass. “We are waiting,” Jessica Myers, a spokeswoman for Garmin, said in a telephone interview.

For most consumers, she said, devices are reliable enough already. Growth in the industry is driven instead by better digital mapping and software, making what already exists more useful. Garmin’s latest car navigator, for example, alerts drivers to traffic jams on the road ahead and the price of gas at nearby stations.

At home at least, the Kremlin is guaranteeing a market by requiring ships, airplanes and trucks carrying hazardous materials to operate with Glonass receivers, while providing grants to half a dozen Russian manufacturers of navigators.

Technically precise they may be, but even by Russian standards, some of the Russian-made products coming to market now are noticeably lacking in convenience features.

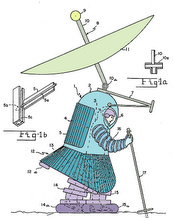

At the Russian Institute of Radionavigation and Time in St. Petersburg, for example, scientists have developed the M-103 dual system receiver. The precision device theoretically operates more reliably than a G.P.S. unit under tough conditions, like the urban canyons of Manhattan.

With its boxy appearance, the M-103 resembles a Korean War-era military walkie-talkie. It weighs about one pound and sells for $1,000, display screen not included. To operate, a user must unfurl a cable linking the set to an external antenna mounted on a spiked stick, intended to be jabbed into a field.

“Unfortunately, we haven’t developed a hand-held version yet,” said Vadim S. Zholnerov, a deputy director of the institute.

By the end of the year, the authorities here say, the Russian space agency plans to launch eight navigation satellites that would nearly complete the country’s own system, called Glonass, for Global Navigation Satellite System.

The system is expected to begin operating over Russian territory and parts of adjacent Europe and Asia, and then go global in 2009 to compete with the Global Positioning System of the United States.

Nor is Russia the only country trying to break the American monopoly on navigation technology. China has already sent up satellites to create its own system, called Baidu after the Chinese word for the Big Dipper. And the European Union has also begun developing a rival system, Galileo, although work has been halted because of doubts among the private contractors over its potential for profits. Russia’s system is furthest along, paid for with government oil revenue.

What is driving the technological battle is, in part, the potential for many more uses for satellite navigation than the one most people know it for — giving driving instructions to travelers. Businesses as disparate as agriculture and banking are integrating it into their operations. Satellite navigation may provide the platform for services like site-specific advertising, with directions that appear on cellphone screens when a user is walking, for example, near a Starbucks coffee shop or a McDonald’s restaurant.

Sales of G.P.S. devices are already booming. The global market for the devices hit $15 billion in 2006, according to the GPS Industry Council, a Washington trade group, and is expanding at a rate of 25 to 30 percent annually.

But what is also behind the battle for control of navigation technology is a fear that the United States could use its monopoly — the system was developed and is controlled by the military, after all — to switch off signals in a time of crisis.

“In a few years, business without a navigation signal will become inconceivable,” said Andrei G. Ionin, an aerospace analyst with the Center for the Analysis of Strategies and Technologies, which is linked to the Russian defense ministry. “Everything that moves will use a navigation signal — airplanes, trains, yachts, people, rockets, valuable animals and favorite pets.”

When that happens, countries that choose to rely only on G.P.S., he said, will be falling into “a geopolitical trap” of American dominance of an important Internet-age infrastructure. The United States could theoretically deny navigation signals to countries like Iran and North Korea, not just in time of war, but as a high-tech form of economic sanction that could disrupt power grids, banking systems and other industries, he said. The United States government’s stated policy is to provide uninterrupted signals globally.

G.P.S. devices, in fact, are at the center of the dispute over the Iranian seizure of 15 British sailors and marines. The British maintain that the devices on their boats showed they were in Iraqi waters; the Iranians have countered with map coordinates that it said showed they had been in Iranian waters.

Russia’s project, of course, carries wide implications for armies around the world by providing a navigation system not controlled by the Pentagon, complementing Moscow’s increasingly assertive foreign policy stance.

The United States formally opened G.P.S. to civilian users in 1993 by promising to provide it continually, at no cost, around the world.

The Russian system is also calculated to send ripples through the fast-expanding industry for consumer navigation devices by promising a slight technical advantage over G.P.S. alone, analysts and industry executives say. Devices receiving signals from both systems would presumably be more reliable.

President Vladimir V. Putin, who speaks often about Glonass and its possibilities, has prodded his scientists to make the product consumer friendly.

“The network must be impeccable, better than G.P.S., and cheaper if we want clients to choose Glonass,” Mr. Putin said last month at a Russian government meeting on the system, according to the Interfax news agency.

“You know how much I care about Glonass,” Mr. Putin told his ministers.

G.P.S. has its roots in the American military in the 1960s. In 1983, before the system was fully functional, President Ronald Reagan suggested making it available to civilian users around the world after a Korean Air flight strayed into Soviet airspace and was shot down.

G.P.S. got its first military test in the Persian Gulf war in 1991, and was seen as a big reason for the success of the precision bombing campaign, which helped spur its adoption in commercial applications in the 1990s.

The Russian system, like America’s G.P.S., has roots in the cold war technology to guide strategic bombers and missiles. It was briefly operational in the mid-1990s, but fell into disrepair. The Russian satellites send signals that are usable now but work only intermittently.

To operate globally, a system needs a minimum of 24 satellites, the number in the G.P.S. constellation, not counting spares in orbit.

A receiver must be in line of sight of no fewer than three satellites at any time to triangulate an accurate position. A fourth satellite is needed to calculate altitude. As other countries introduce competing systems, devices capable of receiving foreign signals along with G.P.S. will more often be in line of sight of three or more satellites.

Within the United States, Western Europe and Japan, ground-based transmissions hone the accuracy of signals to within a few feet of a location — better than what could be achieved with satellite signals alone. The Russian and eventual European or Chinese systems, therefore, would make receivers more reliable in preventing signal loss when there are obstructions, like steep canyons, tall buildings or even trees.

Still, a Glonass-capable G.P.S. receiver in the United States, Western Europe or Japan would not be more accurate than a G.P.S. system alone, because of the ground-based correction signals. In other parts of the world, a Glonass-capable G.P.S. receiver would be more reliable and slightly more accurate.

American manufacturers that are dominant in the industry could be confronted with pressure to offer these advantages to customers by making devices compatible with the Russian system, inevitably undermining the American monopoly on navigation signals used in commerce.

In this sense, the Russians are setting off the first salvo in a battle for an infrastructure in the skies. Russia sees a great deal at stake in influencing the standards that will be used in civilian consumer devices.

The market for satellite navigators is growing rapidly. Garmin, the largest American manufacturer, more than doubled sales of automobile navigators in 2006, for example, and in February it showed a Super Bowl ad that was seen as a coming of age for G.P.S. navigators as a mass market product.

Jeremy D. Ludwig was one consumer who said he would be willing to pay a slight premium for a device equipped with a chip capable of processing Russian navigation signals.

He recounted a recent trip on Interstate 25 in Colorado, when, he said, he was dismayed to discover the G.P.S. device on his BlackBerry had inexplicably lost its signal, just as he was trying to decide which exit to take into Denver.

“If you don’t know which exit to take, you’re already lost,” Mr. Ludwig, an art student, said in a recent telephone interview from Colorado Springs.

That kind of attitude is what Russia is banking on even as it also takes a stab at making consumer receivers — so far without much success. But the Russian goal of diversifying navigation signals used in commerce will be achieved, Mr. Ionin said, even if foreign manufacturers simply adopt the Russian standard, and even if Russia’s own attempt to make consumer devices fails.

To encourage wide acceptance, Mr. Putin has been pitching the system during foreign visits, asking for collaboration and financial support.

Now, only makers of high-end surveying and professional navigation receivers have adopted dual-system capability.

Topcon Positioning Systems of Livermore, Calif., for example, offers a Glonass and G.P.S. receiver for surveyors and heavy-equipment operators. Javad Navigation Systems is built around making dual-system receivers, with offices in San Jose and Moscow.

Javad Ashjaee, the president of Javad, said in an interview that wide adoption was inevitable because more satellites provided an inherently better service. “If you have G.P.S., you have 90 percent of what you need,” he said. Russia’s system will succeed, he said, “for that extra 10 percent.”

Adding Glonass to low-end consumer devices would require a new chip, with associated design costs, but probably not much in the way of additional manufacturing expenses, he said.

Already this year, in a sign of growing acceptance of Glonass, another high-end manufacturer, Trimble, based in Sunnyvale, Calif., introduced a Russian-compatible device for agricultural navigators, used for applying pesticides, for example.

Whether consumer goods manufacturers will follow is an open question, John R. Bucher, a wireless equipment analyst at BMO Capital Markets, said in a telephone interview.

Garmin, which has more than 50 percent of the American market, has not yet taken a position on Glonass. “We are waiting,” Jessica Myers, a spokeswoman for Garmin, said in a telephone interview.

For most consumers, she said, devices are reliable enough already. Growth in the industry is driven instead by better digital mapping and software, making what already exists more useful. Garmin’s latest car navigator, for example, alerts drivers to traffic jams on the road ahead and the price of gas at nearby stations.

At home at least, the Kremlin is guaranteeing a market by requiring ships, airplanes and trucks carrying hazardous materials to operate with Glonass receivers, while providing grants to half a dozen Russian manufacturers of navigators.

Technically precise they may be, but even by Russian standards, some of the Russian-made products coming to market now are noticeably lacking in convenience features.

At the Russian Institute of Radionavigation and Time in St. Petersburg, for example, scientists have developed the M-103 dual system receiver. The precision device theoretically operates more reliably than a G.P.S. unit under tough conditions, like the urban canyons of Manhattan.

With its boxy appearance, the M-103 resembles a Korean War-era military walkie-talkie. It weighs about one pound and sells for $1,000, display screen not included. To operate, a user must unfurl a cable linking the set to an external antenna mounted on a spiked stick, intended to be jabbed into a field.

“Unfortunately, we haven’t developed a hand-held version yet,” said Vadim S. Zholnerov, a deputy director of the institute.

Last modified: April 04. 2007 12:00AM

No comments:

Post a Comment