WITH A CELLPHONE AS MY GUIDE

location based services

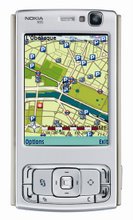

Think of it as a divining rod for the information age. If you stand on a street corner in Tokyo today you can point a specialized cellphone at a hotel, a restaurant or a historical monument, and with the press of a button the phone will display information from the Internet describing the object you are looking at. The new service is made possible by the efforts of three Japanese companies and GeoVector, a small American technology firm, and it represents a missing link between cyberspace and the physical world. The phones combine satellite-based navigation, precise to within 30 feet or less, with an electronic compass to provide a new dimension of orientation. Connect the device to the Internet and it is possible to overlay the point-and-click simplicity of a computer screen on top of the real world. The technology is being seen first in Japan because emergency regulations there require cellphones by next year to have receivers using the satellite-based Global Positioning System to establish their location. In the United States, carriers have the option of a less precise locating technology that calculates a phone's position based on proximity to cellphone towers, a method precise only to within 100 yards or so. Only two American carriers are using the G.P.S. technology, and none have announced plans to add a compass. As a result, analysts say Japan will have a head start of several years in what many analysts say will be a new frontier for mobile devices. "People are underestimating the power of geographic search," said Kanwar Chadha, chief executive of Sirf Technology, a Silicon Valley maker of satellite-navigation gear. The idea came to GeoVector's founders, John Ellenby and his son Thomas, one night in 1991 on a sailboat off the coast of Mexico. To compensate for the elder Mr. Ellenby's poor sense of direction, the two men decided that tying together a compass, a Global Positioning System receiver and binoculars would make it possible simply to point at an object or a navigational landmark to identify it. Now that vision is taking commercial shape in the Japanese phones, which use software and technology developed by the Ellenbys. The system already provides detailed descriptive information or advertisements about more than 700,000 locations in Japan, relayed to the cellphones over the Internet. One subscriber, Koichi Matsunuma, walked through the crowds in Tokyo's neon-drenched Shinjuku shopping district on Saturday, eyes locked on his silver cellphone as he weaved down narrow alleys. An arrow on the small screen pointed the way to his destination, a business hotel. "There it is," said Mr. Matsunuma, a 34-year-old administrative worker at a Tokyo music college. "Now, I just wish this screen would let me make reservations as well." Mr. Matsunuma showed how it works on a Shinjuku street. He selected "lodgings" on the screen. Then he pointed his phone toward a cluster of tall buildings. A list of hotels in that area popped up, with distances. He chose the closest one, about a quarter-mile away. An arrow appeared to show him the way, and in the upper left corner the number of meters ticked down as he got closer. Another click, and he could see a map showing both his and the hotel's locations. Mr. Matsunuma said he used the service frequently in unfamiliar neighborhoods. But it came in most handy one day when he was strolling with his wife in a Tokyo park, and he used it on the spur of the moment to find a Southeast Asian restaurant for lunch. The point-and-click idea could solve one of the most potentially annoying side effects of local wireless advertising. In the movie "Minority Report," as Tom Cruise's character moved through an urban setting, walls that identified him sent a barrage of personally tailored visual advertising. Industry executives are afraid that similar wireless spam may come to plague cellphones and other portable devices in the future. "It's like getting junk faxes; nobody wants that," said Marc Rotenberg, director of the Electronic Privacy Information Center, a policy group in Washington. "To the degree you are proactive, the more information that is available to you, the more satisfied you are likely to be." With the GeoVector technology, control is given over to the user, who gets information only from what he or she points at. The Ellenbys have developed software that makes it possible to add location-based tourism information, advertising, mobile Yellow Pages and entertainment, as well as functions for locating friends. Microsoft was an underwriter of GeoVector development work several years ago. "We believe we're the holy grail for local search," said Peter Ellenby, another son of John Ellenby and director of new media at GeoVector. The GeoVector approach is not the only way that location and direction information can be acquired. Currently G.P.S.-based systems use voice commands to supplement on-screen maps in car dashboards, for example. Similarly, many cellphone map systems provide written or spoken directions to users. But the Ellenbys maintain that a built-in compass is a more direct and less confusing way of navigating in urban environments. The GeoVector service was introduced commercially this year in Japan by KDDI, a cellular carrier, in partnership with NEC Magnus Communications, a networking company, and Mapion, a company that distributes map-based information over the Internet. It is currently available on three handsets from Sony Ericsson. In addition to a built-in high-tech compass, the service requires pinpoint accuracy available in urban areas only when satellite-based G.P.S. is augmented with terrestrial radio. The new Japanese systems are routinely able to offer accuracy of better than 30 feet even in urban areas where tall buildings frequently obstruct a direct view of the satellites, Mr. Ellenby said. In trials in Tokyo, he said, he had seen accuracies as precise as six feet. Patrick Bray, a GeoVector representative in Japan, estimated that 1.2 million to 1.5 million of the handsets had been sold. GeoVector and its partners said they did not know how many people were actually using the service, because it is free and available through a public Web site. But they said they planned in September to offer a fee-based premium service, with a bigger database and more detailed maps. Juichi Yamazaki, an assistant manager at NEC Magnus, said the companies expected 200,000 paying users in the first 12 months. He said the number of users would also rise as other applications using the technology became available. NEC is testing a game that turns cellphones into imaginary fly rods, with users pointing where and how far to cast. Another idea is to help users rearrange their furniture in accordance with feng shui, a traditional Chinese belief in the benefits of letting life forces flow unimpeded through rooms and buildings. The market in the United States has yet to be developed. Verizon and Sprint Nextel are the only major American carriers that have put G.P.S. receivers in cellphone handsets. "The main problem is the carriers," said Kenneth L. Dulaney, a wireless industry analyst at the Gartner Group. Although some cellular companies are now offering location-based software applications on handsets, none have taken advantage of the technology's potential, he said, adding, "They don't seem to have any insight." Sirf Technology, which makes chips that incorporate the satellite receiver and compass into cellphones, said they added less than $10 to the cost of a handset. Several industry analysts said putting location-based information on cellphones would be a logical step for search engine companies looking for ways to increase advertising revenues. Microsoft has already moved into the cellular handset realm with its Windows Mobile software, and Google is rumored to be working on a Google phone. According to the market research firm Frost & Sullivan, the American market for location-based applications of all kinds will grow from $90 million last year to about $600 million in 2008. It is perhaps fitting that the elder Mr. Ellenby, a computer executive at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in the 1970's, is a pioneer of geolocation technology. In the 1980's he founded Grid Computer, the first maker of light clamshell portable computers, an idea taken from work done by a group of Xerox researchers. A decade later a Xerox researcher, Mark Weiser, came up with a radically different idea — ubiquitous computing — in which tiny computers disappear into virtually every workaday object to add intelligence to the everyday world. Location-aware cellphones are clearly in that spirit. Article Link on The New York Times

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment