Google Maps Is Changing the Way We See the World

location based services

In 1765, a 22-year-old British naval officer named James Rennell set out to map the entire Indian subcontinent. Traveling with a small party of soldiers, he used the advanced technologies of the day: a compass and a distance-measuring wheel called a perambulator. During the six-year journey, one soldier was killed by a tiger, five were mauled by a leopard, and Rennell was wounded in an attack by angry locals. He survived, and his detailed maps and atlas, published in the 1780s, defined British understanding of India for generations. Years later, a British geographer wrote that, to Rennell, "blanks on the map of the world were eyesores." More than two centuries later, within the decidedly safer confines of Building 45 on Google's Mountain View, California, campus, John Hanke clicks the 3-foot image of Earth projected on his office wall and spins it around to India. Hanke, the director of Google Earth and Google Maps, zooms in for a closer look at Bangalore. At first, the city appeared in Google Earth as little more than a hi-res satellite photo. "Bangalore wasn't mapped on Google's products," he says, "and it really wasn't very well mapped, period."

Now, however, hundreds of small icons pop up on the screen. Pointing at one brings up a text bubble identifying a location of interest: a university, a racetrack, a library. An icon hovering over the Karnataka High Court calls up a photo of its bright red exterior and a link to an account of its long, distinguished history. Another, atop M. Chinnaswamy Stadium, links to a Wikipedia entry about the legendary cricket matches played there. "As you can see, it's very well mapped now," Hanke says, pulling up a photo of a Hindu temple.

The annotations weren't created by Google, nor by some official mapping agency. Instead, they are the products of a volunteer army of amateur cartographers. "It didn't take sophisticated software," Hanke says. "What it took was a substrate — the satellite imagery of Earth — in an accessible form and a simple authoring language for people to create and share stuff. Once that software existed, the urge to describe and annotate just took off."

Discovering the New World7 glimpses into the hyperlocal future.

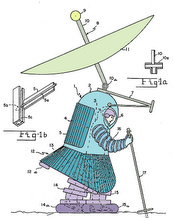

The Internet of ThingsWhat if you could walk down an unfamiliar street, use your camera phone to take a picture of a building, and instantly know everything about it, from the architect to the list of tenants. The technology to make common objects clickable, like hyperlinked words on a Web site, is available today in the form of 2-D barcodes. These digital tags look like empty crossword puzzles. Users create them online, print them out, and paste them around the city. Then anyone with a phonecam can "click" on them. A program on the phone decodes the pattern and redirects the curious pedestrian to a Web page. One project, called Smartpox, is using these barcodes to build online communities that center around, for example, scavenger hunts and restaurant reviews. Members slap a barcode on a given establishment, and in-the-know passersby can get the dirt on its crème anglaise. At Semapedia.com, you can drop in any Wikipedia URL to instantly generate a 2-D barcode pointing to the corresponding entry.

A career in cartography used to be the prerogative of well-funded adventurers — men like Rennell or Lewis and Clark — with full government backup. Even after the advent of commercial satellite and aerial photography, the ability to make maps remained largely in the hands of specialists. Now, suddenly, mapmaking power is within the grasp of a 12-year-old. In the past two years, map providers like Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo have created tools that let anyone with an Internet connection layer their own geographic obsessions on top of ever-more-detailed road maps and satellite images. A host of collaborative annotation projects have appeared — not to mention tens of thousands of personal map mashups — that plot text, links, data, and even sounds onto every available blank space on the digital globe. It's become a sprawling, networked atlas — a "geoweb" that's expanding so quickly its outer edges are impossible to pin down.

There are the narrowly focused maps, like hidden mountain-biking trails, local restaurant favorites, and annotated travel guides. Then there are the more elaborate efforts, all of which "give people the power to create their own ground truth," says Mike Liebhold, a senior researcher specializing in geospatial technology at Silicon Valley's Institute for the Future. When a large fire broke out in Georgia in April, a resident quickly built a regularly updated map showing the burn areas. In Indonesia, for which Google still has no underlying road map, someone is tracing routes over satellite photos to create his own. The US Holocaust Memorial Museum recently released an annotated layer in Google Earth that displays the Darfur genocide in horrifying geographic detail, showing burned villages and linking to photos and videos.

if (typeof drawDropCap == "function") {

var arrExcludeDivs = new Array("article_itemlist");

drawDropCap("articletext", arrExcludeDivs);

}

Add this to:

Digg

Del.icio.us

Sphere

Full Page

Page:

1

2

3

4

5

next

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment