GPS survey can improve farm’s bottom line

location based services

Inaccurate acreage estimates could lead to some farmers spending too much or too little on producing their crops, according to an LSU AgCenter watershed agent, who says the cost of more accurate surveys may be worth the investment.

“Precision agriculture is putting the right stuff in the right place at the right time, and the first step is to find out how large your field really is,” said Tom Hymel, an LSU AgCenter agent working in the Teche-Vermilion, Atchafalaya and lower Red River watershed basins in southwestern Louisiana.

Overestimating acreage could be an expensive mistake because all inputs are acreage-based. And input recommendations usually are based on research results obtained from work conducted on accurately measured plots, Hymel said.

Most producers rely on acreage estimates made by government agencies, which use detailed aerial photographs taken from several thousand feet overhead. But Hymel said such factors as a shadow caused by a tree line can result in significant inaccuracies.

Although they can cost several thousand dollars, Hymel says estimates made using global position system (GPS) equipment can be much more precise, and experts say the more accurate measurements can make major differences for farmers.

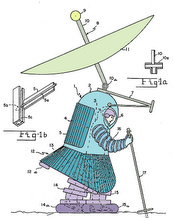

The GPS surveys are conducted using an antenna mounted on an all-terrain vehicle that follows the perimeter of a field. Using that system, ditches, odd-shaped fence lines and irregular shapes can be accurately measured.

Agricultural consultant Blaine Viator said almost half of his clients are going to GPS surveys. “More and more growers are seeing the need for it — once they see the errors,” Viator said. “What we’ve found on average, a farm ends up with 7 percent less acreage.”

A 7 percent mistake could mean a farmer is paying an additional 7 percent in expenses to grow a crop, since aerial applicators charge for their services on a per-acre basis. And usually, acreage estimates by federal agencies don’t include levees or ditches as non-productive areas.

A farmer would be more pleased with the production and associated profit margin of 100 tons of cane on 950 acres than the same tonnage on 1,000 acres, he said.

Handheld GPS units lack the precision to get an accurate measurement, Hymel added, but many agricultural consultants have the proper equipment.

The LSU AgCenter agent said he has seen several examples of surprising results.

For example, crawfish acreage in St. Martin Parish had been reported at 28,000, but a GPS survey conducted by Hymel showed the actual figure at 20,000 acres.

Hymel said a farmer told him after getting a GPS survey he applied herbicides and was able to estimate so closely that the last jug of chemical was just enough to finish the last field.

Hymel said he found many variances on a sugarcane farm. Almost half of the farm’s 164 fields were inaccurate by at least 5 percent, and the overall discrepancy was 7 percent.

“More of them were overestimated than underestimated,” he said, adding that the average underestimate was off by 5.8 percent and the average overestimate was off by 7.2 percent. “We had some that were off as much as 30 percent,” he said.

The LSU AgCenter agent said he plans to continue with the GPS work in the spring by picking a farm to use in a demonstration project.

Farmer Rene Simon of Iberia Parish said more accurate surveys allow for more accurate calibration of spray rigs. “Your fertilizer applications are much more accurate.”

Since cane harvesters lack yield monitors, determining acreage with some degree of accuracy also can provide basic yield information. Harvests on some fields may seem too high or too low because of erroneous acreage estimates, but the GPS work reveals the discrepancies.

Simon said farmers also are using GPS to make straighter rows, which can improve spraying efficiency. “You might think you’re in the right spot and might have a marker, but with GPS you’re dead on the money,” he said.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment