Dreams of a Truly Mobile Web

Net Needs to Escape Its Computer Cage,But Best of Luck Freeing It in the U.S.

location based services

It's a longstanding maxim of this column that the future generally doesn't arrive with a lot of flash and noise -- instead, it sneaks up on you. One day you notice you're reading your news online, banking via PC and downloading stuff from eMusic, and try to remember the last time you flipped through the physical newspaper, wrote a paper check or bought a CD.

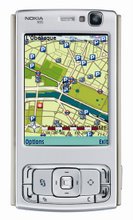

But not always. Last week the New York Times' John Markoff and Martin Fackler wrote about a Japanese service that allows people to use their cellphones to guide them to hotels and other services: For instance, select a nearby hotel and your phone will use GPS technology and a built-in compass to guide you there. GeoVector (www.geovector.com), the San Francisco company at the heart of the service, touts other "location-aware" services, such as the ability to aim smart binoculars at racing yachts and get the name of the boat and its current statistics.

"Our goal is to let people access information when they need it most -- when they're in the real world," says Peter Ellenby, GeoVector's director of new media.

GeoVector's services are an effort to solve an increasingly vexing problem: Too many of the Internet's more-advanced functions still aren't truly mobile. Sure, the Net is exploding with wonders and is increasingly good at offering local information -- but for our purposes those wonders remain largely caged in PCs and laptops. Sit at your computer and you can study up on bars in the West Village, Revolutionary War landmarks in lower Manhattan or Chelsea antique stores. But take that knowledge out into the real world and you'll probably be stuck with scrawled notes or a sheaf of printouts -- which instantly become useless if there's a change in plans or you come across something unexpected in your travels. After researching and planning online, being cut off from the Net is painful: It's as if your home and office PCs are air pockets you wind up swimming between, hoping you can hold your breath long enough.

There are whizzy PC applications that attempt to bridge the gap. Google Earth comes preloaded with local-search capabilities, letting you hunt for bars or antique stores or anything else and plot them on a satellite photo. Google has made it easier for developers to tinker with Google Earth, and any number of organizations and hobbyists have marked up data to work with the program, letting you overlay the God's-eye view with, say, real-estate listings you can further explore, or information about historic sites.

Still, Google Earth doesn't work quite so well when you zoom down to street level, which is where it's ultimately needed most: It has a feature that turns on "buildings" for some geographic areas, but the buildings are featureless gray monoliths. Amazon's A9 search engine offers a feature called Block View that shows street-level photos of your destination and the surrounding blocks. (You'll find Block Views, where available, when you search via A9's Yellow Pages.) Sounds great in theory; in practice, not so much: When I hunted for one lower Manhattan bar I know all too well, I got a photo of a vacant lot several blocks to the west. The bar had been photographed, but when I found it, the facade was almost completely blocked by a parked UPS truck.

Imagine a mash-up of Google Earth and an improved Block Views and you've got something pretty compelling -- a link-ripe "virtual city" that would overlay whatever real city you happen to be in. Unfortunately, such a program would be stuck on your PC, where it wouldn't do you much good -- in the U.S., surfing the Web via cellphone or PDA is painful if you're doing much beyond seeking a simple answer to a specific question.

Broadband services for cellphones, PDAs and host of other objects could help free the Net's advanced functions, and location-based services like GeoVector's could help merge them with the street-level real world: Point a "location-aware" device with a GPS receiver and a compass at an object, and all sorts of things become possible, beyond navigation and concierge-style services. A digital camera could record information about the landmark it's shooting. Aim your cellphone at the third baseman (who has a GPS-enabled chip in his uniform), and you can review his stats. Or play "Doom" in a real city, with virtual monsters waiting at certain coordinates. (GeoVector has helped gamers do just that in Auckland, New Zealand.)

"Our philosophy is the world itself is a gigantic database and almost everything out there has some kind of geolocated reference," Mr. Ellenby says, adding that "I think it will be second nature for people to pick up any kind of mobile device and point it at something and get information from the real world. Just like now it's second nature to turn on your PC and pick up the mouse."

Sounds cool -- but something was nagging at me. Where had I encountered this idea before? Then I remembered: In William Gibson's 1994 novel "Virtual Light," bike messenger Chevette Washington swipes a pair of virtual-light glasses that send information about what the wearer's looking at directly to his or her optic nerves. As one character notes, a landscape architect wearing them would go for a walk and see little labels identifying every tree and plant. (GeoVector's founders were inspired by their own experience: As they told the Times, they thought of their idea on a 1991 sailing trip while struggling to match up navigational landmarks with maps. Why couldn't you just point a device at a geographical feature and be told what it is?)

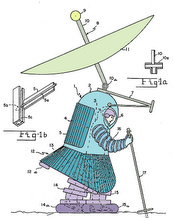

Chevette Washington's VL glasses turn out to be loaded with secret business information, which puts her life in danger. (Saying more would risk ruining the book.) But if you'll indulge me in a bit of science fiction, imagine smart glasses that know where they are, what direction you're facing, and have a broadband connection and can show you maps, reference photos of what you're apparently looking at, or just about anything else you could find online.

Mr. Ellenby says Mr. Gibson's glasses are about 20 to 30 years away ("Virtual Light" is set in 2005 -- oh well), but that doesn't stop him from musing about the possibilities. Imagine looking at the Acropolis or Gettysburg and seeing a recreation of what happened there, giving yourself a tour of a city's history at your own pace and inclination, or looking at a construction site and seeing a visualization of the finished building. To say nothing of how easy it would be to get directions, find a retailer, or perform a host of other mundane functions that are now easy on a PC but can be aggravating in the real world.

"If you want to find out about your surroundings, you'll turn on your glasses," Mr. Ellenby says.

(Incidentally, GeoVector's current services don't require devices that see -- it's the combination of a GPS receiver and a compass that lets a device deduce what you're looking at. Potential results are ordered by distance and by category: If you were at a baseball game, you could indicate whether you wanted to buy a replica jersey like the one worn by the fan in front of you, review the right fielder's stats, or look at famous plays in stadium history by focusing on the outfield wall.)

If even GeoVector's current services sound like science fiction, to an unfortunate extent they are -- in the U.S. Why does it seem like our cellphones and PDAs do so much less than Japan's? Blame a combination of factors -- but above all, blame the four big U.S. wireless companies.

The carriers have the final call on what hardware can use their networks and what software can be downloaded onto their phones, and their track record isn't one of encouraging innovation beyond what they can control and extract ready profit from. (Walt Mossberg wrote the definitive lament for this state of affairs.) A byproduct of this wireless sclerosis: A great deal of cellphone advertising focuses on boasts that Company A's service stinks less than Company B's. That doesn't exactly encourage customers to try whatever whizzy new services are allowed to reach to market -- if your cellphone can't reliably get a signal, why would you think it could point you to a boutique hotel?

Mr. Ellenby doesn't hide his frustration with this situation, arguing that "the carriers need to be a lot more creative in how they deal with content and application makers in the U.S., I think, for things to take off over here."

Mr. Ellenby thinks MVNOs (telecom slang for mobile virtual network operators, companies that target niche markets and have lease arrangements with a big carrier) will be the first to offer location-based services in the U.S. In the meantime, while GeoVector keeps talking to carriers world-wide, its focus remains on Japan -- leaving Mr. Ellenby to accentuate the positive.

"We have 90 million customers, potentially," he says, adding: "That's a lot of customers."

What's your vision of a truly mobile Internet that could be accessed from cellphones or PDAs? How would it interact with the real world? Write to me at realtime@wsj.com -- comments will be posted periodically in Real Time. If you don't want your comments considered for Real Time, please make that clear.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment