Matching Digital Maps to America's Ever-Changing Roads

location based services

SATELLITE navigation systems have largely delivered all they promised when the technology first took to the highway: that drivers would always know where they were.

Skip to next paragraph

RelatedMaps More Real Than Virtual

Uli Seit for The New York Times

When there are holes in the map data, geographic analysts have to do a little detective work.

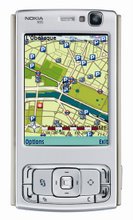

The trouble is, there are times when simply knowing your position on the planet is not enough. A G.P.S. unit is of little help in guiding you to a chosen destination when the route it calculates is outdated, if it instructs you to take an exit that has been closed or if it tells you to turn onto a road that has been converted into a pedestrian mall.

Technically speaking, you are not lost, but it's still a frustrating case of "can't get there from here."

To cope with this situation, digital mapping companies are rushing to keep up with road construction projects and new subdivisions popping up in what were cornfields only yesterday. Their goal is to assure that the digital maps used by navigation systems, stored on a DVD, hard disc or memory card, do not lag too far behind the reality.

The task is huge. On any given day at Navteq, the nation's largest digital map company, as many as 550 field analysts in 131 offices around the world may be on the road charting street grids. One recent bright and breezy afternoon in the far reaches of Queens, two of the company's analysts were navigating their white Ford Escape around quiet streets in the Rockaway Peninsula.

"I think you can delete what's in front of us because that doesn't exist anymore," Chris Arcari, a Navteq geographic analyst told his colleague, Shovie Singh, who was serving as the map plotter on this excursion.

Mr. Arcari was referring to the scene ahead, where a street that once ran through a new condominium development had been torn up and barricaded with "road closed" signs. The last time he and Mr. Singh were mapping the neighborhood — just a couple of months ago — the road went all the way through.

That's how quickly maps can become obsolete.

Using a graphics tablet — a computer input device used to mark up the map by drawing with a pen instead of clicking a mouse — Mr. Singh made a series of yellow X's over the closed road, which was displayed on a computer monitor on the dashboard.

The analysts record every little change they find. A stretch of West 66th Street on the Upper West Side of Manahattan, which has been renamed Peter Jennings Way to honor the late television anchorman, is now listed under both names on their maps. A series of crosstown streets in Midtown that were recently designated as "through" streets — no left or right turns off the streets are allowed during peak traffic hours — are now all marked as such so navigation systems will not instruct drivers to make turns.

The mapping system aboard the Ford Escape is relatively simple. It consists of a G.P.S. receiver with a roof-mounted antenna; an electronic input tablet; and a laptop computer that transfers raw geographic data accumulated on the drive to a monitor between the driver and the plotter, as Navteq calls the analyst in the passenger-side seat. There is also a video camera used to make a visual record of the trips.

The electronics record the vehicle's exact path, as determined by the G.P.S. unit. The data that the analysts see is much less refined than the maps that end up in a vehicle's navigation system. To the untrained eye, it is an undecipherable jumble of cartography symbols and color-coded lines.

Red lines represent major arteries, light blue lines are closed roads, blobs of blue mark non-navigable areas like marshes or fields, and so on. The equipment can code 150 attributes for any given road, noting details from how many lanes there are to whether the stretch of pavement is part of an underpass.

When there are holes in the map data — missing addresses, a road that was not indicated or a landmark with no name — the geographic analysts have to do a little detective work.

For instance, a short road on the Rockaway Peninsula — it dead-ends into a canal — has been unnamed on Navteq maps for some time now. Mr. Arcari pulled the Escape to the side of the road, got out and inspected a mailbox to see if the street name was there. No luck. In such a case, he will consult New York City records and use whatever name appears there for the street.

Map technicians spend a lot of time trying to match city and county records across the country with the actual roads. They verify and reverify, making trips into the field several times a week so their data will be reliable for car companies, makers of accessory and hand-held G.P.S. units and Internet map providers like Google and Yahoo.

Navteq updates its database continuously, releasing new versions several times a year so its customers are not selling maps that are long out of date. But as long as G.P.S. units depend on digital maps stored onboard — the satellite's signal provides information only to determine a position, not the street grid itself — they are always going to have some holes because road networks are constantly evolving.

And with navigation systems becoming more and more sophisticated, offering features like the locations of A.T.M.'s or Italian restaurants nearby, it is a never-ending undertaking to keep data current.

"You see changes all the time," Mr. Arcari said. "There are new turn restrictions, street directionality, speed limits."

Navteq, based in Chicago, and Tele Atlas, a competitor with headquarters in Belgium, gather all this information and create the databases for companies that sell navigation systems and services. While Tele Atlas relies more on existing data sources and less on fieldwork to update its records, the companies' methods of making a digital map have similarities. The raw information — geographic coordinates of latitude and longitude — is stored with other essential details as a data file called a vector map.

Once field analysts are done charting streets and points of interest and the information has been added to the map file, the data can be sold to companies like Garmin, Magellan and auto industry suppliers, which then convert the map data into a form that can be displayed on vehicle navigation system screen. Technicians at the G.P.S. companies encode the maps into a format appropriate for their systems, writing the software that controls functional features like the soothing electronic voices that announce directions.

For consumers, keeping a navigation system up to date requires purchasing a new digital map. Automakers typically issue annual updates for their systems; most recent models require a new map DVD at $200 and up. (One for a Cadillac Escalade or a Jeep Grand Cherokee is $199, while the latest Lexus update is about $350.)

Owners should check with their dealers for special replacement programs. General Motors, for example, is offering owners of 2006 models free update discs after the first and second years.

Maps for handheld G.P.S. units need to be updated as well, usually by uploading the new data to a memory card. An update for Garmin's popular MapSource unit is $75.

Next Article in Automobiles (2 of 22) »

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment