Where 2.0 Gives the World Meaning

location based services

SAN JOSE, California (37°19'58.28"N 121°53'22.00"W ) -- At O'Reilly Media's Where 2.0 conference this week, an odd mix of people gathered and gawked at a tiny spy plane mounted on a display table. Some wore the understated ties of government bureaucrats, others had wrinkled T-shirts with obscure open-source jokes on them, while a third tribe focused on the plane's electronics package with the preternaturally fascinated expressions of academics.

Stephen Morris, whose company MLB sells the 25-pound unmanned vehicles for $50,000 a pop, didn't care who these people were -- as long as they wanted to hear about his drag-and-drop UI for steering the planes, he was going to keep talking. He slid a plane icon onto a map with a mouse. "You send the plane off with instructions to photograph a certain area, and you can get 3-inch-per-pixel images," Morris enthused. "Most of my customers are military and government, but there are commercial applications too."

Everybody nodded, then made room for a new round of gawkers. At the Where Fair, the nighttime entertainment at the conference, every display was maximally enticing to location geeks. That's what brought this diverse crowd of 800 people together: technologies that produce information about location, whether a spy plane, an API for web-mapping applications like Google Maps, or a geolocation hack that pinpoints people's positions using Bluetooth, Wi-Fi access points or cell-phone towers.

At another table, a web developer named Christopher Schmidt showed off his system for locating himself on a map using nothing more than a tiny Python application on his Nokia phone and a Bluetooth-enabled GPS device. When he's not working for map-sharing site Platial and map-analysis company MetaCarta, Schmidt spends his time wandering around his hometown of Cambridge, Massachusetts, using his custom cell-phone software to unmask the ID numbers on each GSM cell tower he passes. Then he associates that tower ID with a GPS-defined location, and uploads it to his website.

When his electronic surveying is complete, Schmidt will have a system that can tell him where he is at all times -- without GPS -- by triangulating the signals from the newly mapped cell towers.

Calling himself a "neogeographer," Schmidt is part of a generation of coders whose work is inspired by easily obtained map data, as well as the mashups made possible by Google Maps and Microsoft's Virtual Earth.

Undoubtedly, the most interesting map geekery was coming out of a growing group of open-source programmers who've devoted themselves to liberating the tools once used by experts to do geographical analysis. Schuyler Erle, co-author of Mapping Hacks, said the open-source community has focused on all the things you can't do in Google Maps. "We can browse Google Maps, but the look and feel of those maps is fixed," he explained. "We want the flexibility to tell our own stories with maps. What's exciting is the ability to do your own cartography, to put your own labels on and show your own roads."

Erle is part of the Open Source Geospacial Foundation, or OSGeo, and like many of his fellow neogeographers he hangs out informally on an e-mail list called Geowanking. The members of OSGeo run mapping software projects, including the open-source version of Autodesk's MapGuide, and a powerful tool for producing maps with metadata called OpenLayers.

"Most web maps out there give you 'red dot fever,' which means that they're covered in red dots whose meaning is hard to decipher," Erle said. "But with OpenLayers, you can create meaningful symbols on your maps. You can make maps that show demographics or property values or erosion." Other members of OSGeo, sitting nearby, began to chime in and offer ways to use OpenLayers -- civic activists could make maps to explain issues to zoning boards; environmentalists might make maps that show the results of clear-cutting.

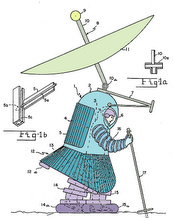

University of California at Davis soil science graduate student Dylan Beaudette gave a talk about one way to use an OSGeo tool called the Geographic Resources Analysis Support System, or GRASS. He figured out how to chart paths through the wilderness that include the fewest slopes. "I don't really like to hike hills," he confessed. Using GRASS' elevation-analysis tools, he plotted a trail off the beaten path through a park near his family's cabin -- a path that emulated the way a drop of water would flow. As a result, the trail never went uphill. "I haven't actually walked this trail yet," he conceded. "But I will this summer." By then, Beaudette said, he will also have perfected a method for determining where the most shade was, and will reprogram his trail accordingly.

"We want map-analysis tools to be as ubiquitous as spreadsheets," Erle summed up. "Everybody should be able to do geo-analysis."

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment