'Mashup' websites are a hacker's dream come true

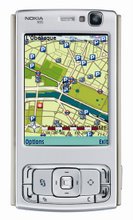

location based services

TAKE an online map of a city, throw in some information on local house prices or crime levels, and you have the recipe for a "mashup" website.

Mashups, so-called because they are created by merging data from two or more websites, have been steadily growing in popularity thanks to the useful way they present local information. However, the informal manner in which these websites are thrown together means that information displayed on them could be inaccurate or false. Issues such as security and privacy may only be considered as an afterthought, if at all, and there is nothing to prevent people using them to obtain personal information, such as addresses. John Musser, who runs www.programmableweb.com, an influential site that chronicles the mashup phenomenon, says privacy is rarely considered.

Mashups merge location-based information with other online sources to create an application that amounts to more than the sum of its parts. For instance, www.chicagocrime.org combines Google Local's maps with Chicago's crime database, pinpointing the city's crime hotspots. At www.housingmaps.com, houses for sale advertised on craigslist.org are injected into Google Maps, allowing users to see the location of properties they are interested in. Other mashups plot traffic camera positions, allowing users to choose a camera and take a look at the jams. Still others highlight places where photobloggers have taken snaps or allow travellers to map their journeys. About 10 mashups per week are being added to the web, according to analysts' estimates.

Creating a mashup has never been easier. Initially, programmers had to hack into the mapping systems to work out how to plug location data into them. That changed when the major mapping site owners - Google, Yahoo and Microsoft - recognised that they could gain exposure from a mashup. They now freely publish application programming interface (API) software that allows latitude and longitude data to be injected into their maps, whether it is the address of a sports club or the location of a traffic snarl-up. The mashup culture is also getting a boost from more powerful computers: PCs can now redraw maps with updated data in real time, according to Bret Taylor, product manager for Google Maps in Santa Clara, California.

The worry is that mashups could be an accident waiting to happen, according to some delegates at the Computer-Human Interaction conference in Montreal, Canada, last month. Hart Rossman, chief security technologist for Science Applications International of Vienna, Virginia, and adviser to the US Department of Defense, warned that developers of these websites are not taking issues such as data integrity, system security and privacy seriously enough. That matters because many millions of dollars are already being invested in some mashup sites, particularly those related to the travel market, and people are beginning to depend on these sites for everyday tasks such as avoiding traffic queues on the way to work.

Central to the problem is the fact that the mashup developer does not own the data being mashed, while the owner neither knows nor cares that their data is being used. "How do you know the data is real?" Rossman asks. Without an exchange of encrypted ID certificates between source and mashup, the data could be coming from a hacker's "spoof" site, he warns.

A hacker could feed false data to a crime location mashup, for example, perhaps to help raise property prices in a particular area by making it appear crime-free. A prankster could create bogus traffic jams on a mashup map, diverting traffic in such a way that queues are actually made worse.

Privacy is a particularly worrying issue because mashup sites have no clear rules on what they can and can't do with people's details. To demonstrate how easily mashups can combine information in a way that invades people's privacy, computer consultant Tom Owad mashed book wishlists posted by Amazon users with Google Maps. The wishlists often contain the user's full name, as well as the city and state in which they live - enough information to find their full street address from a search site such as Yahoo People Search. That is enough to get a satellite image of their home from Google Maps. Owad used this to produce a map of people who liked to read "subversive" books (www.applefritter.com/bannedbooks), showing what level of detail the sites can throw up.

"Mashups have no clear rules on what they can and can't do with people's details"

Computer viruses are also a threat, as they could be designed to target mashups. Rossman says a "mashup worm" might track back to the site's source of information, such as a photoblog, news site or crime database, and corrupt it. "Something unfortunate could happen to the owner of the data," Rossman says. "We have to know the privacy, security and data integrity implications of mashups, otherwise litigation becomes a possibility."

Mashup proponents see the point, but are not yet totally convinced. Taylor believes it's too early to be getting heavy-handed with security. "Small mashups are too new and self-contained for all this right now, but the bigger venture-capital-backed sites may well need more policing," he says.

Ben Metcalfe, project leader of the BBC's online developer network Backstage, which encourages mashups of the corporation's RSS news feeds, TV listings and traffic information, agrees that privacy needs to be addressed. "There are issues, such as at the mashup logging-in stage," he says. For example, a site that mashes a photoblog with a map site will need your photoblog subscription details, including your username and password, to do so. This gives the site access to your entire collection of personal photographs, and how it then handles access to this information is a grey area. "It is one of the things the mashup scene needs to think about," Metcalfe says. Taylor agrees: "Both Flickr and Google Maps have this problem with passwords being passed around. There's no real control."

This is not the case across the board, though. Some organisations are introducing measures to control the way their data is used. eBay has a clear, strong privacy policy that people using its API must obey. And while it is technically possible for someone to take a BBC news feed into a mashup and tamper with the information, they would be breaking the terms under which the news feed is supplied. "They have to maintain the integrity of our data or they lose the feed," Metcalfe says.

Security improvements needn't cost a fortune, even for amateur developers creating mashups in their spare time. Rossman says a small investment could make a big difference. "It only costs $60 a year for an SSL certificate that authenticates a server. Mashup developers need to act now before security breaches hit the newspapers," he says.

From issue 2551 of New Scientist magazine, 12 May 2006, page 28

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment