- The Economist | GPS, PDAs, SatNav, GeoTags, Social Networks - Converge and Monetize

-

PERSONAL navigators—those turn-by-turn digital finders usually mounted on car dashboards, with touch screens and pre-loaded maps—have become this holiday season’s must-have gizmo. They account for seven of Amazon.com’s 20 top-selling electronic products this month.

Over the past year, global sales of such gadgets have doubled to 30m units. That’s small beer compared with annual sales of mobile phones or MP3 players. But with prices tumbling 20% annually, GPS (global positioning system) devices have reached a “tipping point” that has pitched them into mainstream acceptance.

Jupiter images Bring it with you

Bring it with youThis has happened faster than anyone expected, and for one simple reason: they’ve become small and light enough to make them portable. Untethered from the dashboard, personal navigators now travel as much with the owner on foot as with the car on the highway. In so doing, the device is morphing into something different and even more useful.

Thank Moore’s Law for a start. The relentless doubling of processor power every 18 months or so has endowed such devices with enough speed and storage to cope with ever-richer mapping tasks. Meanwhile, battery developments pioneered by mobile-phone makers have allowed portable navigators to run all day on a single charge.

Add a broadband wireless connection to location data from GPS satellites, digital maps packed with millions of “points of interest”, spoken street names and directions, and the navigation gizmo ceases to be a passive tool. Instead, it becomes alive with real-time information about where precisely (within 15 yards) you are on the planet and what’s happening nearby.

With a wireless connection, a portable navigator can add additional content to its map, such as minute-by-minute changes in traffic and weather conditions. Dynamic data like that then make it easy to provide alternative routes.

Last month, TomTom, a Dutch GPS-maker, launched a product that routes cars around traffic jams. Using a wireless connection, the subscription-based service collects traffic data by anonymously tracking the movement of mobile phones through their cellular network. Where the phone bleeps concentrate is where the snarl-ups are.

Adding connectivity to navigation doesn’t stop there. It can also be used to search the internet for local content while on the move. Input your likes and dislikes beforehand, and the device will search for things you might find interesting en route—an outlet of your favourite coffee chain, record store or Japanese restaurant, an old movie you’ve been meaning to see, or a popular hangout for folks your own age and inclination. Users have barely begun to tap navigation tools for their social-networking potential.

Also, instead of showing merely generic icons for hotels, restaurants, petrol stations and stores, mobile maps with broadband connections can be fed specific logos for, say, McDonald's, Shell or Gap. Even better, outlets can embed their latest offerings, discounts or seasonal menus within their clickable logos displayed on the map. Suddenly it becomes easy to find the cheapest place to gas up or have lunch.

Real-time parking information is another service that’s set to change our driving habits. Merely showing the location of a car park is useless if the lot is full. What motorists need to know beforehand is whether there are any empty slots, and does the lot accept validation from nearby stores and restaurants. Adding such features to personal navigation gear is relatively easy once the device is connected to the internet.

As navigation technology broadens its scope, it is changing its role. Until now, it has been used to guide people to their destinations. These innovations are turning it into a mobile tool to find things of personal interest along the way. That makes the route as much an input as an output—and the journey at least as important as the destination.

Other things change once mobile navigation steps out of the car and takes a hike. For instance, the “granularity” of the information displayed has to be finer. The kind of information that’s perfectly adequate for driving along the highway at 30mph is nowhere near detailed enough for walking at 3mph. In a car, “coming up soon” means in the next mile or so; on foot, it means literally the next block.

In addition, the nature of the route becomes as important as the distance. Motorists can use service roads and side streets as well as main roads and freeways without hesitation. By contrast, pedestrians can’t use freeways, but they can take short-cuts up steps, along walkways and footpaths, and across parks, plazas and open ground.

Pedestrians also need to know more about the “topology” of the route they’re being told to follow. Where hills barely bother motorists, they are a serious concern for people on foot. Where motorists look out for street signs, pedestrians watch for landmarks and special buildings like post offices, libraries, schools and petrol stations.

A mapping company called Tele Atlas uses a fleet of vans equipped with GPS and video cameras to record how individual streets actually look to walkers. Enriching maps with a worm’s (rather than bird’s) eye view—with real 3D images of stores and other roadside features—makes life easier for pedestrians and motorists alike.

All of which suggests map-making is the key to this rapidly changing field. Knowing where precisely individuals are at any given instant—and what retail outlets and other establishments they are near—is central to mobile searching and to location-based advertising. That’s why the two leading digital-mapping companies, Tele Atlas and Navteq, have lately been the target of takeover bids.

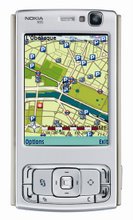

Earlier this week, Navteq, based in Chicago, formally accepted an $8.1 billion offer from Nokia, the world’s largest mobile-phone maker. Last month, Garmin, a Kansas City-based GPS-maker, withdrew its $3.3 billion hostile bid for Tele Atlas, leaving the map-maker to rival TomTom.

That Nokia paid so much for Navteq shows how important location-based information is becoming to mobile-phone companies. In a recent survey by J.D. Power and Associates, over 40% of respondents wanted GPS on their phones. Only 26% thought WiFi would be handy, and 19% would opt for television.

Mobile phones and navigation gear are clearly converging. By offering connectivity, mobile-search and location-based services (including route directions), both are chasing the same market: a rising generation of footloose, gregarious and acquisitive consumers.

Is there room for both platforms? Possibly. Their different strengths and forms should continue to differentiate them.

Smart phones will always be more compact and provide better voice connections, thanks to their proprietary cellular networks. By contrast, personal navigators will continue to offer bigger touch-sensitive screens, larger hard-drives and faster broadband connections. That will make them better for watching streaming video and television as well reading the fine-grained information and 3D imagery now being packed into navigation maps.

Enthusiasts will presumably want both. Having dropped enough hints over the past few weeks, your correspondent hopes to be opening a new one of each on Christmas Day.

http://www.economist.com/daily/columns/techview/displaystory.cfm?story_id=103...

Saturday December 15, 2

Saturday, December 22, 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment